Prize-winning Polish film on refugees opens to government backlash | Poland

A prize-winning film sharply critical of the Polish government’s attitude to refugees has opened at cinemas across the country, after being attacked in the run-up to its release by members of the Polish government.

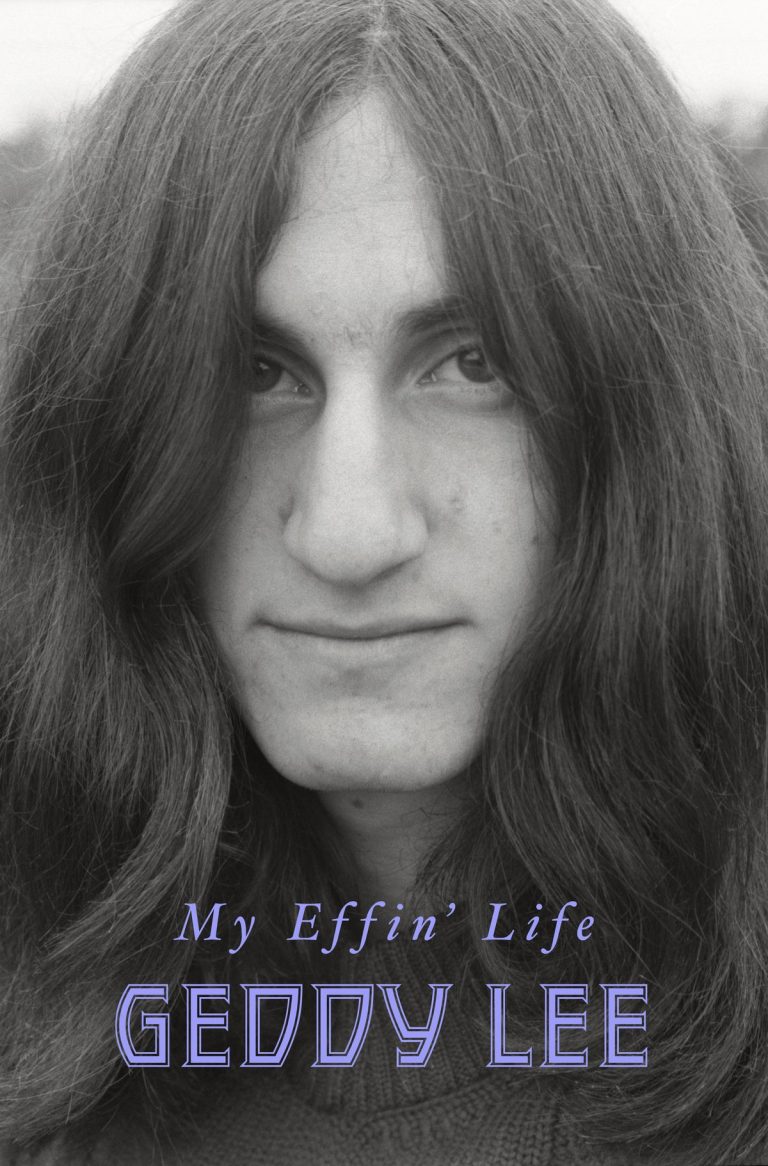

Green Border, a feature film by the celebrated director Agnieszka Holland, won the special jury prize in Venice last month. It tells the story of a Syrian family trying to get to Europe via the Belarus-Poland border in 2021, and the brutal treatment they receive at the hands of Polish border guards.

The justice minister, Zbigniew Ziobro, compared the film to a Nazi propaganda movie “showing Poles as bandits and murderers”, despite admitting he had not watched it. The deputy interior minister, Błażej Poboży, called the film a “disgusting libel” that is “harmful to the Polish state and Poles”.

In a telephone interview, Holland said the venom of the government reaction has taken her by surprise.

“I expected waves of hate and propaganda and denial, but instead of waves we have a tsunami. I didn’t expect that within a few days, three or four times, the ministers of justice, interior, president of the country and numerous others would be attacking me on such a level of hate and aggression,” she said.

Holland said she felt the issue of migration “is one of the most important challenges for the future of Europe and the world”, and she was motivated to make the film by anger over how the government responded to Poland becoming a migration route two years ago.

“I saw that the authorities tried to organise a laboratory of lies and violence, and take political advantage of the misery of people,” she said. She casted for the refugee characters in France and Belgium, among actors who had become refugees.

Far-right activists demonstrate against in front of a banner reading ‘Putin thanks Agnieszka Holland’. Photograph: Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto/Shutterstock

The film has become a key talking point in an increasingly vitriolic campaign ahead of a parliamentary elections next month. The nationalist ruling coalition, led by the Law and Justice (PiS) party, has focused its campaign on migration, and on the wall it constructed on the border with Belarus to keep out refugees.

Speaking of the film’s positive reception among some Poles, the prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, said: “This red carpet is only a preview of the red carpet that PO [the main opposition party] is rolling out for illegal immigrants, a red carpet that threatens to destabilise our homeland.”

Holland said it was not deliberate that the film opened in the weeks before the election, but said she hoped that after watching it viewers would reconsider their views about people stranded at the border.

“It’s different you know, you see some interviews and documentary clips, and then if you see everything with your own eyes and identify with full characters,” she said.

Activist groups say at least 49 people have died and 200 are missing since the crisis began at the border in 2021, and people continue to die at the border even now.

Agnieszka Holland receives her special jury prize award for Green Border at the Venice film festival this month. Photograph: Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

Agnieszka Holland receives her special jury prize award for Green Border at the Venice film festival this month. Photograph: Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

One character in the film is a border guard who is horrified and traumatised by the things he is forced to do and attitudes of his colleagues. “I consider the border guards also as victims, they have been forced to break the law and do things they are not trained for,” said Holland.

Poboży said the government had commissioned “a specially prepared clip that shows the elements that were missing in this film”, praising the work of border guards, and would ask cinemas to show it before screenings of the film. It is not clear whether cinemas will comply with the request.

President Andrzej Duda also criticised the film, suggesting it would have been better to make a film about the Polish response to Russia’s war in Ukraine. He said: “Millions of Poles opened their hearts and welcomed Ukrainians into their homes. How do those people feel today when they see that a renowned director, instead of making a film about Poles opening their hearts … is making a film slandering Poles and Poland?”

The end of the film makes the explicit comparison between the two refugee crises, and the different receptions granted to Ukrainians and to the much smaller number of darker-skinned refugees from Africa and the Middle East received at the border.

The film shows the hellish reality of so-called “pushbacks” in the forest, where Belarusian soldiers force people to keep trying to get into Poland, and Polish border guards ignore their asylum applications and dump them back across the border into Belarus. The Belarusian dictator, Alexander Lukashenko, has been widely accused of facilitating the refugee route through his country in order to put pressure on Poland and the EU.

Green Border is not a subtle film, and it subjects the viewer to numerous scenes of violence that are shown in detail rather than merely implied.

“I decided not to be discreet and to make some kind of parabolic stylistic choices, I wanted people to experience what those people are experiencing who are going though it, both the victims and the soldiers,” said Holland.