‘The perpetrators were people like us’: the burden of history at Auschwitz | Second world war

“Where does the story of Auschwitz begin?” asked our guide as we walked towards the Arbeit Macht Frei sign marking the entrance to the former death and concentration camp. With the birth of Adolf Hitler? With the codifying of Nazi ideology? With the first deportation of Polish prisoners to the military barracks that became a killing factory? There were no right answers, he said.

Last month, less than 48 hours after Hamas militants slaughtered men, women and children in Israel, and as references to “pogroms” and “massacres” were resurfacing in the headlines, I found myself taking part in a long-planned seminar at the Auschwitz Memorial. It was a coincidence we were there at that time, and equally coincidental that among those taking part were Jewish journalists and a Palestinian camera operator born in Israel.

He – a Christian from Haifa – was repeatedly asked how he felt about what was happening in his homeland. He was appalled by the Hamas massacre and despairing that Israel would exact a far heavier price on the Palestinian population of Gaza. “Why do I have to take sides?” he asked. “Why can’t I be horrified by the actions of both sides?”

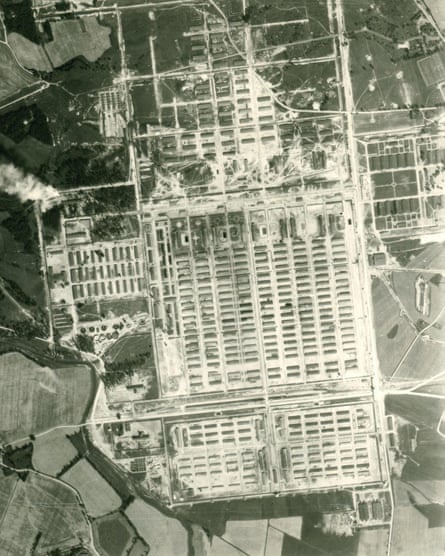

Aerial view of Auschwitz taken by the RAF. Photograph: Aerial Reconnaissance Archives/PA

As we tramped through the rain and mud of Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II (Birkenau) – where 1.3 million people were held, 1.1 million of whom perished, including 1 million Jews, up to 75,000 Poles, 20,000 Roma and Sinti and 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war as well as prisoners from elsewhere in Europe – the burden of history was on us. As a non-Jew it was beyond horrifying, but it was impossible to feel its physical weight as the Jews with us, who had lost family here, did.

Even the Jewish American Holocaust educator who had spent her life learning about and lecturing on Auschwitz was surprised to discover new details. Paweł Sawicki, the press officer for the Auschwitz Memorial and our guide, said historians were making discoveries every day – and not just from documents, but from pieces of bone and the dust from cremated bodies that still surface almost 80 years after the camp was liberated.

What makes Auschwitz so human and inhuman are the small details: the child’s red shoe; the suitcase marked with a name and address; a tin prosthetic leg; a miniature coffin with a charred bone inside; the upside down B in ARBEIT (a deliberate act of defiance by its makers? Nobody knows, but to some prisoners it became a sign that the Nazis could dictate their lives and deaths but could not control everything). There are the “Prussian blue” stains around the barrack room door caused by the oxidation of hydrogen cyanide and iron in the walls, where Zyklon B gas was used as a pesticide to de-louse prisoners before the Germans discovered it could be effectively used to kill insect and host. There is the potato peeler found in the luggage of someone who expected to live to prepare vegetables.

The upside down B in the Arbeit Macht Frei sign at the entrance to the camp. Photograph: Martin Argles/The Guardian

The upside down B in the Arbeit Macht Frei sign at the entrance to the camp. Photograph: Martin Argles/The Guardian

Sawicki ran through history and facts without hyperbole or comment. They are bad enough undressed.

The story of Auschwitz, he said, was the story of dehumanisation, of us and them, of perpetrators and prisoners. In the Nazi camp, the latter were divided into useful and useless: one group was kept alive for as long as they retained a function, which was not long with starvation rations, typhus epidemics and a selection of collective punishments, then exterminated. The other group was murdered straight away.

Paweł Sawicki, a guide at the Auschwitz Memorial. Photograph: Kim Willsher/The Guardian

Paweł Sawicki, a guide at the Auschwitz Memorial. Photograph: Kim Willsher/The Guardian

Only Jews were subject to immediate selection on arrival at Auschwitz II, a vast camp known as Birkenau. Stepping off the freight wagons, those deemed useless – women, children, elderly and disabled people – were immediately herded towards the gas chambers and crematoria. We know the rest. They were ordered to strip, told they were taking a shower, and poisoned with Zyklon B gas. Their bodies were burned first in pits, then, as the extermination operation became more sophisticated, in furnaces. The ashes were thrown into the river or scattered over fields. Another detail was given to us: the Germans were so stingy with their crematorium fuel that some bones did not completely burn and had to be smashed.

There was little panic because the Nazis cynically played on hope: the condemned were told to mark their suitcases and put their clothes on numbered hooks “to find them later”. As we know, there was no later. Those waiting naked to enter the gas chamber might hear the screams of the dying, but by then their fate was already sealed. Right or left, crematorium or camp made little difference in the end. For the vast majority of Jewish prisoners, death came sooner or later.

Hungarian Jews arriving at Birkenau in German-occupied Poland in June 1944. Photograph: Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Hungarian Jews arriving at Birkenau in German-occupied Poland in June 1944. Photograph: Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

In one of the last transports in 1944, the Nazis sent 430,000 Jews from Hungary to Birkenau in eight weeks – the equivalent of 6,000 a day. Three quarters were murdered immediately. The numbers are incomprehensible but Sawicki was able to identify the face of one condemned woman from a black and white photograph. For one moment the inhuman was made human.

“Auschwitz is a human story,” he said, “but we also we need to look at the perpetrators.” By this he meant the SS men and women who ran the camp – only 10% of whom were ever prosecuted for the atrocities they committed. “They did monstrous things but they weren’t monsters. They were people like us, they did what they did then they went home to their families, had dinner … if we want to look for a warning of this, it’s not the tragedy of the victims. It’s the people who chose to do this,” he says.

As Primo Levi wrote in If This Is a Man: “There is no rationality in the Nazi hatred: it is hate that is not in us, it is outside of man. We cannot understand it, but we must understand from where it springs, and we must be on our guard. If understanding is impossible, knowing is imperative, because what happened could happen again.”

One of the other journalists at the seminar was from Sarajevo, a city from which I reported during the war in what was Yugoslavia. Another was from Ukraine. They saw grim echoes of Auschwitz in these conflicts. Not even half a century after 1944, pictures of cadaverous prisoners emerged from the Serbian-run Omarska camp in Bosnia, and another 30 years on we hear reports of Russia holding Ukrainians in “re-education” and “filtration” camps. Now there are reports of Jewish homes in Berlin and Paris, where I live, being tagged with the Star of David.

Perhaps the question is not where the story of Auschwitz begins, but where it ends.