‘The nightmare has ended’: a Pole visits her childhood town after 17 years of exile – archive, 1963 | Poland

Point of arrival

26 November 1963

Last year I went back to Poland to revisit the town where I was born and from which I ran away 17 years ago. I was 15 then and the war had just ended. I had lost my family and my friends and had spent the last two years of the war in hiding among strangers. I lived in fear of denunciation, trying always to be one step ahead of the Gestapo, who followed me from one secret hideout to another.

When it was all over I returned to my home town and found it empty. It is a beautiful town. One of the most ancient in Europe, full of churches and charming old houses. The streets are narrow and cobblestoned. There is an old park where all the children play and where I used to go every day until the outbreak of war. A great river winds in and out between streets spanned by ancient stone bridges. There I stayed in 1945 waiting for my parents and the rest of my family to come back. There I found how and where they had died and when there was no more to find out I fled the town which to me had become a cemetery.

I fled from my memories as far as I could go and finally settled in Australia, vowing never to see Europe again. But after 10 years the wounds healed and I returned to England. And last year, following a blind impulse, I went back to my old town.

It has not changed. Only the inhabitants are new. As I wandered through the crowded streets I thought that no one now would recognise my name or my face. In the town where once every child knew our house I could not, on that first day, find a room for one night.

I passed a flower shop whose owners once lived in our house and I entered, curious to know how they would react. As I stood searching for words, the old woman at the counter suddenly burst into tears and threw her arms around me. Behind her the husband stood rooted to the spot, repeating over and over: “I was with your daddy in the same platoon, back in 1920 … I was with your daddy …”

In this town where a telephone is still a rarity the news of my return spread like fire. I was asked to come to a cafe to meet an old friend and when I entered a crowd rose from the marble-topped tables and advanced with outstretched arms. I spent the next few hours sipping the bitter black coffee and nibbling at cream cakes, listening to all those middle-aged men and women who once knew my parents, went to school with them, worked with father, or took their afternoon tea in this very same cafe with mother.

When all my future meals and nights were finally divided among those present I escaped to the park. Here I had played every day till 1939 as my parents had played before me. Here I was born, in the little clinic hidden among the trees. Here a child spat in my face and called me a Jew. Here I went to the theatre for the first time. And here was the conservatory where in 1945 I briefly tried to continue my musical education.

From this bridge father once jumped fully clothed into the river to rescue a drowning boy. Here I played truant from school while I waited for my parents to return …

The swan pond was empty and overgrown with lilies. The Russians shot all the birds in 1945 and they were never replaced. The glass roofs in the orangery were broken but the old trees were still there and a peacock spread its tail at my approach. I put my arms around a silver birch and knew that I had been right to return.

In the centre of the town, the town hall raises a thin spire which can be seen from almost every part of the town. During my years of exile a recurrent nightmare plagued me, night after night: I was back in my town, trying to reach the central square. I saw the town hall spire but whenever I tried to find my way towards it walls rose from the ground, blocking my passage. Night after night I wandered, exhausted and frightened, with the spire beckoning and always out of reach. When I asked for directions I was met with hostile stares and incomprehensible replies. I could not understand their language. Now I found my way without difficulty and walked around the town hall trailing my hand on its walls.

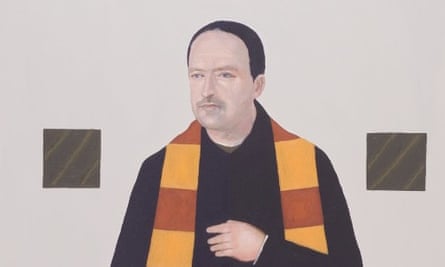

Młynówka Canal and the Church of the Holy Cross. Opole, Poland, 1962. Photograph: aldiami/Herbert Michalke/Alamy

Finally I went to our house. It was occupied by strangers. In 1945 I stood before the door willing myself to ring the bell and finally ran when my courage failed me. Now I walked upstairs and rang the bell. A woman admitted me with a smile. I sat among strange furniture staring at the floor – the same floor surely – while the past rushed back and I knew why I had to come.

I walked around the flat searching for remembered things. I flattened my nose against the nursery window and was greeted by the same view which used to meet me every morning of my childhood. When the woman left the room I kissed the wine-red porcelain stove which has been there all my life. I touched the door frame, thanked the woman, and went out.

As I walked through the darkening streets, my high heels slipping on the cobblestones, I knew that I had come home. There was no need to run any more. In the years of exile I was the only one to remember town, my parents, and my family. Slowly, as the years passed, the image became blurred and I wondered how much of all this I had imagined and how much was true. I began to lose my identity and the rootlessness of my existence almost convinced me that my life had begun suddenly at the age of 18, in Melbourne.

But I came back to find that my memory had served me well. That there were still people who knew my family and could confirm their existence and my own. I found my house, my friends, and my town, which after all the years of foreign travel is still mine. I even found the way to the town hall and the people in the streets spoke the same language as I. The nightmare has ended.