Uncertain waters: the future of Poland’s deepwater container port project

By Agata Pyka and Lena Bäunker

Poland plans to develop a deepwater container terminal within a protected nature reserve in Świnoujście on the Baltic coast. Proponents point to potential economic gains but critics, both locally and in Germany, have raised concerns over the environmental impact and whether local infrastructure can handle the cargo.

On the right bank of the Świna river, house walls are stained grey by dust and coal emissions from the nearby port and liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility. Train tracks cut through deforested patches and wild boar scavenge for food amid roadside litter.

The left bank, in stark contrast, flourishes with lively seaside hotel resorts, attracting over two million tourists each year. They come to the area for its crisp air, expansive beaches and unique biodiversity.

Soon the division of Świnoujście, a port and resort town near the German border, may deepen as Poland’s new ruling coalition continues with the former government’s plans to construct a deepwater container terminal.

The terminal, located beside the LNG facility, will be situated within a nature reserve under the protection of the European Union’s Natura 2000 network.

The Świna and the Baltic Sea (photo credit: Specjal b/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY 2.5)

Activists and some politicians in both Poland and Germany have opposed the project for years, predicting harmful environmental effects and a negative impact on local economies that are reliant on tourism.

Although the European Commission approved the plans in January, citing imperative reasons of overriding public interest, research by Notes from Poland suggests that this decision should be viewed with scepticism.

Underestimated environmental impact

The deepwater terminal is to be built in an area currently home to common eiders and gulls, flounder and herring, and the occasional seal or porpoise.

Approximately 45 hectares of forest and dunes will need to be cleared for port, rail and road infrastructure. Offshore, a container sea bridge, protective breakwater, harbour entrance and turning basin will span around 350 hectares.

To allow 400-metre-long ships access to the port, 13 million cubic metres of seabed will be dredged and disposed of roughly 20 kilometres from the terminal. This will result in increased noise, traffic, emissions and pollution, posing a threat to several unique ecosystems protected under Natura 2000.

EU law and bilateral agreements with Germany required the Polish authorities to conduct an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), allowing construction of the port only if the environment remained largely unchanged or if there were compelling public interests.

A planned „mega port” at Świnoujście in Poland is touted by the Polish government as offering benefits for the entire region.

However, the environmental implications are threatening to cause a rift between Germany and Poland, writes @_EmergingEurope https://t.co/RsMImp8Uer

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 2, 2021

After presenting port plans in 2015, the former Law and Justice (PiS) government took five years to begin the EIA process, following inquiries from Polish MPs.

MEP Hannah Neumann, from Germany’s The Greens, notes that the Polish authorities did not uphold the aforementioned agreements. They provided necessary German translations of documents only when asked and declared the EIA complete before the appeal period had ended.

According to the EIA published in October 2023 by the Regional Directorate for Environmental Protection (RDOŚ) in Szczecin, Poland will take compensatory measures that can adequately protect the affected ecosystems.

These measures include using quiet technologies and relocating the affected Natura 2000 areas to another location. The EIA also anticipates no significant impacts on Natura 2000 areas in Germany.

Activists and politicians from both Poland and Germany challenge these claims.

“It’s unlikely that such a large-scale intervention wouldn’t impact nearby areas. Nature knows no boundaries and operates as an interconnected system,” says MEP Helmut Scholz from Germany’s The Left.

Scholz, in collaboration with his European Parliament colleague Neumann, commissioned an independent assessment of the port project which found that the expansion “would significantly affect flora and fauna on both sides of the German-Polish border.”

Meanwhile Rainer Sauerwein, an activist and retired physicist, has filed a formal appeal with the Polish General Directorate for Environmental Protection (GDOŚ).

Activists Rainer Sauerwein and Norbert Protz (photo credit: Lena Bäunker)

Sauerwein emphasises that Poland’s current EIA only addresses the terminal’s immediate site, ignoring the impact of increased land and maritime traffic. “This oversight neglects amplification effects,” he says. “The EIA fails to assess the full impact scenario from Świnoujście to [German island] Rügen.”

The Polish authorities also announced a new sea access route in early 2023, for which they commissioned a feasibility study on 8 May. It is intended to replace the existing route, which runs partly through German waters and is too shallow for the ships the port in Świnoujście is intended to serve.

Sauerwein suspects political motives behind this decision: “By changing the route, they prevent Germany from saying no.”

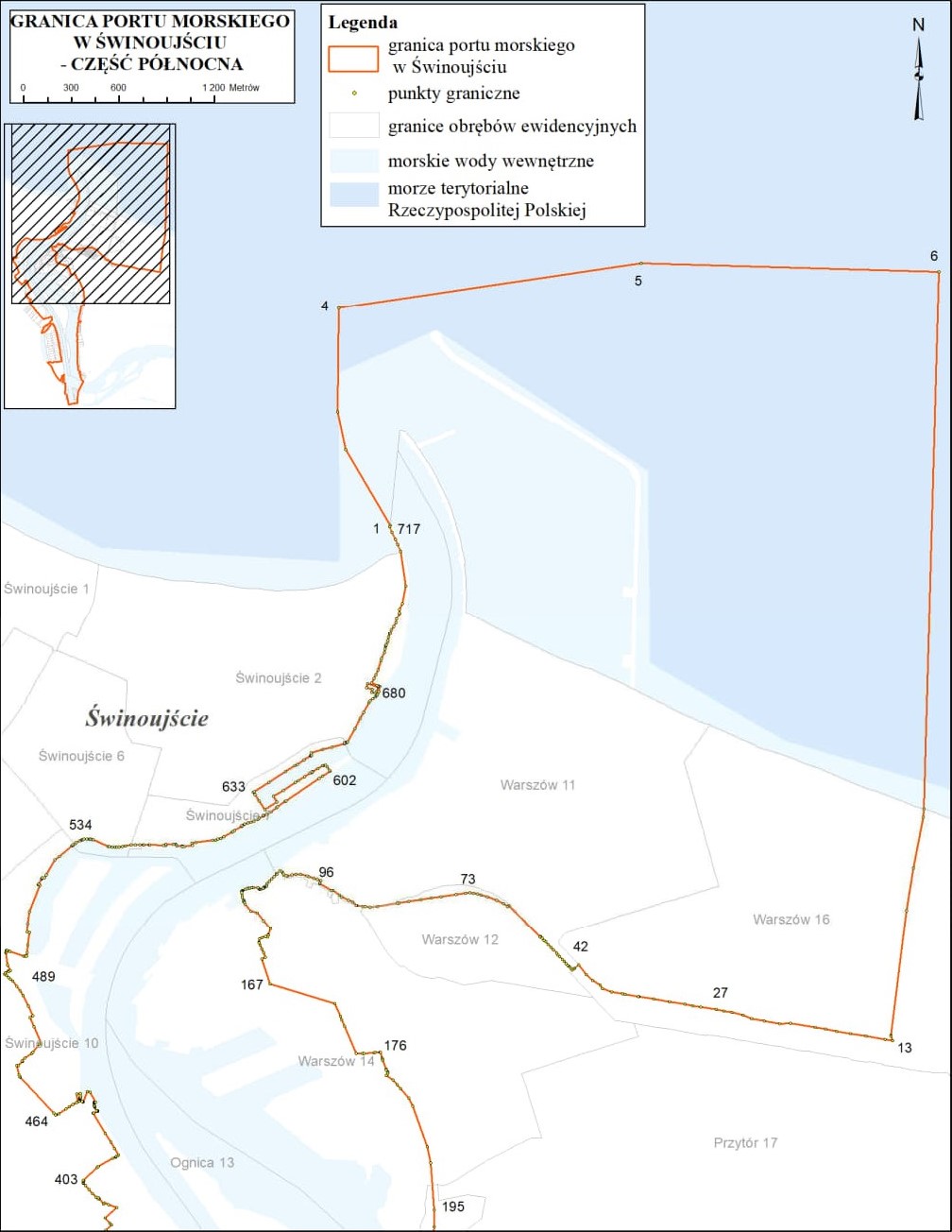

Meanwhile, the Seaports Authority of Szczecin and Świnoujście (ZMPSiŚ) – the body responsible for managing the development of the port – has allocated 500 hectares of land for the project, without detailing their plans.

This decision was introduced through a special bill in the Polish parliament, without consulting the citizens of Świnoujście or the local government, and despite the environmental implications.

A map showing the northern boundary of the land allocated to the Świnoujście port (photo credit: Sejm)

In their response to our inquiry, the ZMPSiŚ gave assurances that the land area of the terminal will not exceed 45 hectares.

“It is mainly an area for the construction of access infrastructure (road and rail) to the terminal and is not equivalent to the felling area. Tree cutting will be carried out only to the extent necessary,” the company wrote.

“If they only need 45 hectares, why take almost 500,” wonders Piotr Piwowarczyk, president of the Świnoujście Tourist Board.

Disputed economic benefits

Last year, the then deputy infrastructure minister Marek Gróbarczyk suggested that the deepwater terminal in Świnoujście would be “a second Hamburg”, referring to Germany’s busiest (and Europe’s third-busiest) seaport.

Numbers available on the project’s website and shared by politicians point to a target handling capacity of two million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit – the size of a standard shipping container) per year. Hamburg handled 7.7 million TEU last year.

Poland will invest 10 billion zloty (€2.1 billion) in developing a container port in the city Świnoujście that can „within 6-7 years become a serious competitor to Hamburg”, says a deputy infrastructure minister https://t.co/G9eR2cLfX8

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 4, 2023

Yet no studies have been conducted to analyse demand for the port’s services, says Rafał Zahorski, an expert in maritime economy who advises both the local and national government.

When asked about this, the ZMPSiŚ claimed that they “have for many years conducted their own analyses of the potential of…the Baltic container shipping market in terms of locating a deepwater container terminal in Świnoujście”.

However, the ZMPSiŚ did not provide us with any materials to evidence this claim.

Likewise, the Polish infrastructure ministry – who also declare to have conducted market assessments – refused to share any documents, citing confidentiality.

Meanwhile, Maciej Brzozowski, a container shipping industry expert and head of the Port of Hamburg’s office in Poland, suggested to business website Money.pl that “so far none of the large shipowners or global terminal operators have been interested in this project”.

Zahorski estimates that the potential capacity should be closer to 400,000 TEU. “But if we take over 200,000 [TEU] it will already be a big success.”

The ferry terminal at Świnoujście, part of the city’s current seaport (photo credit: Kapitel/Wikimedia Commons,under CC BY-SA 4.0)

In order for unloaded containers to be transported across Europe, a network of efficient railways and roads is necessary. Marek Grzybowski, president of both the Baltic Sea and Space Cluster and the Polish Nautical Society, supports the construction of the terminal, but highlights that the current state of infrastructure might hinder its competitiveness.

The E-59 line between Malmö and Vienna connects Scandinavia with Central and Eastern Europe. Its CE-59 branch between Szczecin, Poznań and Wrocław is reserved for freight traffic, however the average speed of cargo trains travelling south on the line from Świnoujście does not currently exceed 20-23 km/h.

By comparison, the speed of trains carrying cargo from German seaports oscillates between 60 and 80 km/h.

“In Poland, one train can load about 80 TEU. Divide even just one million TEU by that, and then by 365 days a year. That’s about 34 trains a day,” Zahorski calculates.

Meanwhile the S3 highway remains under construction. The government considers it “a key transportation corridor that opens Polish ports to central and southern Europe”. But Joanna Agatowska – a former member of the Świnoujście city council and the mayor of the city since April – voices her scepticism.

The S3 highway between Świnoujście and Szczecin is still under construction (photo credit: Zwiadowca21/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 4.0)

“One lane of the S3 highway will be constantly occupied [by freight carriers], so we are left with only one lane for private vehicles,” she says, explaining that tourism in Świnoujście is already decreasing due to road traffic.

According to Agatowska, no buffer parking space has been added along the S3, increasing the likelihood of traffic and road congestion, and not enough space was left to expand the parallel railway.

Zahorski points out that even Germany – a country more experienced in containerisation than Poland – struggled with its own deepwater terminal project. The JadeWeser port opened in 2012 in Wilhelmshaven was designed for 2.8 million TEU, but currently handles only around 500,000 TEU.

Management controversies

Further doubts about the project arise owing to the reputation of its management body, the ZMPSiŚ.

Agatowska feels that the city and its residents have been cheated by both the ZMPSiŚ and the former mayor, Janusz Żmurkiewicz, whose tenure overlapped with the 20 years he spent on the company’s supervisory board until 2020/2021.

As a councilwoman, Agatowska learned about the ZMPSiŚ’s plans to build a deepwater terminal after hearing a rumour from a colleague. She asked Żmurkiewicz about it at a city council session in late 2015, but he denied knowledge of the plans.

However, Żmurkiewicz and the ZMPSiŚ had already made an exploratory visit to the port of Algeciras in southern Spain “with the aim of learning about…an operating model that the Baltic port wants to transfer to its facilities,” reported local broadcaster Radio Bahia Gibraltar at the time.

After being called out by Agatowska, the mayor started to share more information. It emerged that around April 2016, the ZMPSiŚ had hired the consulting company Ernst & Young to conduct an initial economic analysis of the project.

Budowa drogi #S3 w rejonie węzła #Świnoujście Łunowo. Oprócz samego węzła powstaje tu również estakada nad torami kolejowymi, która będzie łączyła z S3 tereny położone na północ od linii kolejowej, w tym planowany port kontenerowy. #ŁączymyPolskę pic.twitter.com/ZVdTZRtVGV

— GDDKiA Szczecin (@GDDKiA_Szczecin) March 6, 2024

Żmurkiewicz promised to conduct a local referendum about the terminal, but it was not held. Agatowska kept pushing for it and was eventually dismissed from her position as chairwoman of the city council.

The ZMPSiŚ continued its activities despite the aforementioned discrepancies. Politicians from the former PiS government made assurances about the necessity of the idea and its bright future.

But the project did not immediately attract investors. The April 2021 tender for its completion saw only one applicant – the UK-based Baltic Gateway Limited, who later turned out to have connections with the ZMPSiŚ board.

The company was not successful in its bid, yet may have created the illusion of interest in the project.

When a subsequent tender was opened, two companies – QTerminals from Qatar and the Belgian-based DEME – were selected to build the terminal and provide measures worth at least €5 million that benefit the local community.

But this amount will not even be enough to cover the road renovation, the cost of which is estimated at €5.5 million, explains Agatowska.

“Both companies are able to withdraw [from the agreement] at the snap of a finger,” adds Zahorski.

Poland has signed a contract with a Belgian-Qatari consortium to construct a new container terminal on the Baltic coast

The government wants the project, which will cost billions of euro, to create a „serious competitor to Hamburg”, the region’s main port https://t.co/XwJX3bEnxI

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 13, 2023

Asked about the two firms, Żmurkiewicz expressed his trust in them but admitted they had not considered the matter of accommodation for future employees.

When asked about the accommodation, the ZMPSiŚ said that “it should be expected that the terminal’s job offer will be aimed primarily at residents of Świnoujście and surrounding towns who have their own accommodation”, in spite of the fact that the city is depopulating.

Neither QTerminals nor DEME responded to our inquiries.

The credibility of the ZMPSiŚ has recently been further undermined by the so-called “pizza gate”, in which an audit showed that pizzeria owner Dariusz Śpiewak – an acquaintance of former PiS minister Joachim Brudzinski – was earning millions of zloty as a company executive employed on favourable terms.

“You know me, I rarely use strong words, but what we are finding at the Seaports Authority of Szczecin and Świnoujście is an absolute scandal,” Arkadiusz Marchewka, a deputy infrastructure minister in the government that replaced PiS in December, wrote in February.

Znacie mnie – rzadko używam mocnych słów, ale to, co zastajemy w Zarządzie Portów Szczecin-Świnoujście to absolutny skandal. Wstępne wyniki trwającej kontroli pokazały, że kolega barona PiS-u Joachima Brudzińskiego zarabiał w porcie miliony. Szef pizzerii wystawiał tej państwowej… pic.twitter.com/gyKnujpFWa

— Arkadiusz Marchewka (@A_Marchewka) February 5, 2024

Despite their initially critical stance towards the terminal and the aforementioned reputation of the ZMPSiŚ, the new Polish government has decided to go ahead with the project.

Owing to the lack of consultation with local residents, Agatowska filed an appeal on 24 May against the West Pomeranian governor’s decision to locate the terminal in Świnoujście, expressing that “such a project has a chance only if it has social acceptance”.

This article has been produced with the support of the Journalism Fund.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Agata Pyka is an assistant editor at Notes from Poland. She is a journalist and a political communication student at the University of Amsterdam. She specialises in Polish and European politics as well as investigative journalism and has previously written for Euractiv and The European Correspondent.

Lena Bäunker is a freelance journalist from Germany currently residing in the Netherlands. She focuses on climate and social justice, as well as political communication, and has contributed to publications such as ZEIT ONLINE, Perspective Daily, Krautreporter, fluter, and Euro News Green, among others.

Main image credit: Port Szczecin-Świnoujście