Wagner: How much of a threat does mercenary group actually pose in Belarus?

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails

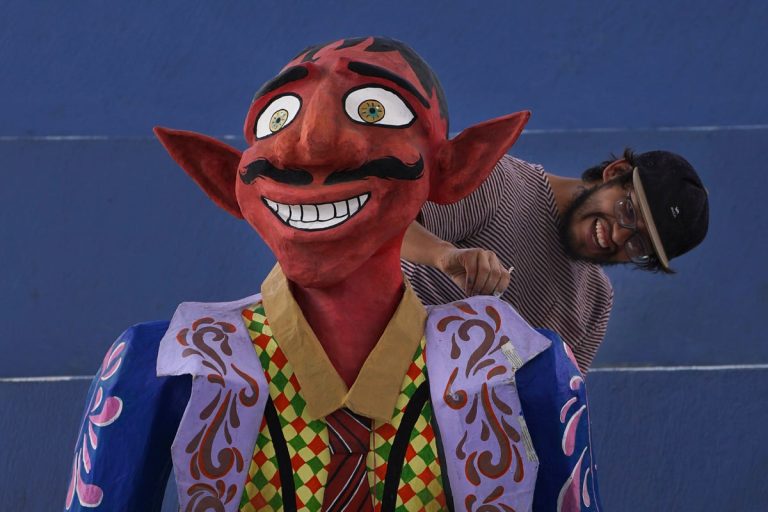

The newfound presence of Wagner mercenaries in Belarus, exiled from Russia after their mutinous march on Moscow, has fuelled fresh anxieties in Ukraine and on Nato’s eastern flank.

Belarus’s neighbours have moved to a heightened state of alert since dictator Alexander Lukashenko appeared to broker a last-minute deal with the Kremlin to defuse the short-lived mutiny on 23 June and host Wagner troops on Belarusian soil.

During a recent meeting at the strategically important Suwalki Gap, a sparsely populated land corridor near their countries’ borders with Belarus and Russia’s enclave of Kaliningrad, Lithuania’s president Gitanas Nauseda warned that north of 4,000 mercenaries were believed to be in Belarus, while Poland’s premier Mateusz Morawiecki branded them “extremely dangerous”.

Wagner mercenaries have been taking part in training with Belarus’s military

(Belarusian Defence Ministry/Handout via REUTERS)

Poland is sending 10,000 troops to its eastern border, and this week held its largest military parade in decades, as it warned that Wagner mercenaries had moved towards Grodno and set up camp in the Brest region, some six miles from Poland’s border.

A group associated with Ukraine’s military has also warned that the construction of a “tent city” capable of housing 1,000 mercenaries some 15 miles from its border could be used to simulate a threat there, in a bid to detract from Kyiv’s efforts to make painstaking gains along the heavily mined front line of Russia’s invasion in the south, and defend a push by Moscow’s forces near Kupiansk in the north.

The true extent to which Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin’s guns for hire are now operating in Belarus – and their aims there – remains hard to determine.

“We are dealing with layer upon layer of disinformation,” said Keir Giles, a senior consulting fellow at Chatham House. “Not only the repeated information campaign trying to convince Ukraine that there is a renewed threat from the north, but also confusion over exactly what Wagner is doing, who they are reporting to, who they are following orders from, and where they might be.”

These factors make it hard to distinguish how much of the threat is “manufactured” to pile pressure on Belarus’s neighbours, Mr Giles said, adding: “The simple answer is that we don’t know. We should watch what is actually being done rather than what is being said.”

(Datawrapper/The Independent)

However, Mark Galeotti, director of the Mayak Intelligence consultancy, said he believed Ukraine’s military was not “in the slightest bit worried” about the threat of Wagner attempting to cross its northern border.

Speaking of claims the mercenaries could try to cross into Poland or Ukraine, he said: “In some ways, Wagner is a victim of its brand name, and people are suggesting it’s going to do all types of crazy things that are totally beyond their capabilities, but also which frankly no one would even try.”

Wagner has “lost all of its heavy equipment”, he added, with Russia’s defence ministry making “damn sure” to reclaim tanks and artillery handed to the mercenaries while in Ukraine, meaning “we’re talking about a bunch of guys with Kalashnikovs, rather than a sort of fully coherent mechanised force”.

Wagner mercenary chief Yevgeny Prigozhin’s whereabouts are unclear

(Reuters)

Citing reports that funding disputes have already seen some mercenaries bussed back to Russia, Mr Galeotti said Ukraine has “ample forces to stop 2,000 guys with guns wandering over” a border “carefully watched” due to its proximity to Kyiv, most likely including by Nato.

While he believes Wagner would not pose much of a direct threat even if better equipped, Nick Reynolds, the Royal United Services Institute’s research fellow for land warfare, said the possibility of disruption “can’t be discounted”.

Read more: Wagner tracker: Charting Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mercenary group through the Ukraine war

Wagner’s presence – along with that of Belarusian and Russian forces – means Ukraine does have to devote some troops to guard the border, which already comes under “a lot of artillery and drone strikes”, albeit not as heavily as troops along front lines in the Donbas and further south, he said.

While Poland’s concerns have been stoked by Mr Lukashenko’s jibes that the country should thank him for constraining Wagner mercenaries he claimed wish to “[smash] up Rzeszow and Warsaw”, the Belarusian leader vowed in February that Minsk would only enter the war if attacked by Ukraine.

Mr Reynolds said he did not foresee any real threat from Belarus this year due to the weakness of Minsk’s military and Russia’s presence there being “just not strong enough to credibly pose a threat of opening a second front” – although Moscow’s mobilisation efforts mean “that might change in time”.

Ukraine has ‘ample forces to stop 2,000 guys with guns wandering over’ a border ‘carefully watched’ due to its proximity to Kyiv

(Genya Savilov/AFP via Getty Images)

“Something I’d watch much more closely in the short-term is Wagner’s international footprint,” he said, adding that the group’s compromised position within Russia itself could see it lean more heavily on its activities in Africa and the Middle East, which are of “enormous value diplomatically” to the Kremlin.

Mr Giles also warned that “forces taking orders from Russia or Belarus do not need to be large or well-equipped to cause disruption”.

He pointed to the “migrant dumping campaign” initiated by Belarus in 2021, with its Baltic neighbours in Warsaw, Vilnius and Riga once again accusing Minsk in recent days of sending asylum seekers en masse to the border in a bid to pile pressure on them.

And he highlighted the power of Wagner “as an information weapon”, whether to distract Ukraine or “throw some kind of provocation with Poland to try to back the fiction that Lukashenko presents to his people of Poland being an aggressive and threatening neighbour”.

Alexander Lukashenko, a close ally of Vladimir Putin, vowed in February that Minsk would only enter the war if attacked by Ukraine

(Mikhail Klimentyev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP)

Dr Marina Miron, of King’s College London’s war studies department, agreed that an attempted incursion doesn’t make “any kind of sense” logistically, saying: “I think it’s more of a kind of psychological operation than anything else. At least for now.”

While the risk is currently low, “at some point, they will be returning to Ukraine”, said Dr Miron. “That’s when there will be a definite threat.”