A stormy start to a much-needed debate on migration in Poland [Opinion]

Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Daniel Tilles

OPINION

Poland is already a country of mass immigration, but politicians have been reluctant to acknowledge it. The last week has finally seen the start of a much-needed debate on how the country should respond to its new reality.

The numbers are striking. In 2023, Poland issued 642,789 first residence permits to immigrants from outside the EU. That was more than any other member state – ahead of Germany (586,144), Spain (548,697), Italy (389,542) and France (335,074).

And this was no anomaly, Poland has issued the bloc’s most permits for the last seven years running. For a couple of years before that, it was second only to the UK, which has since left the EU.

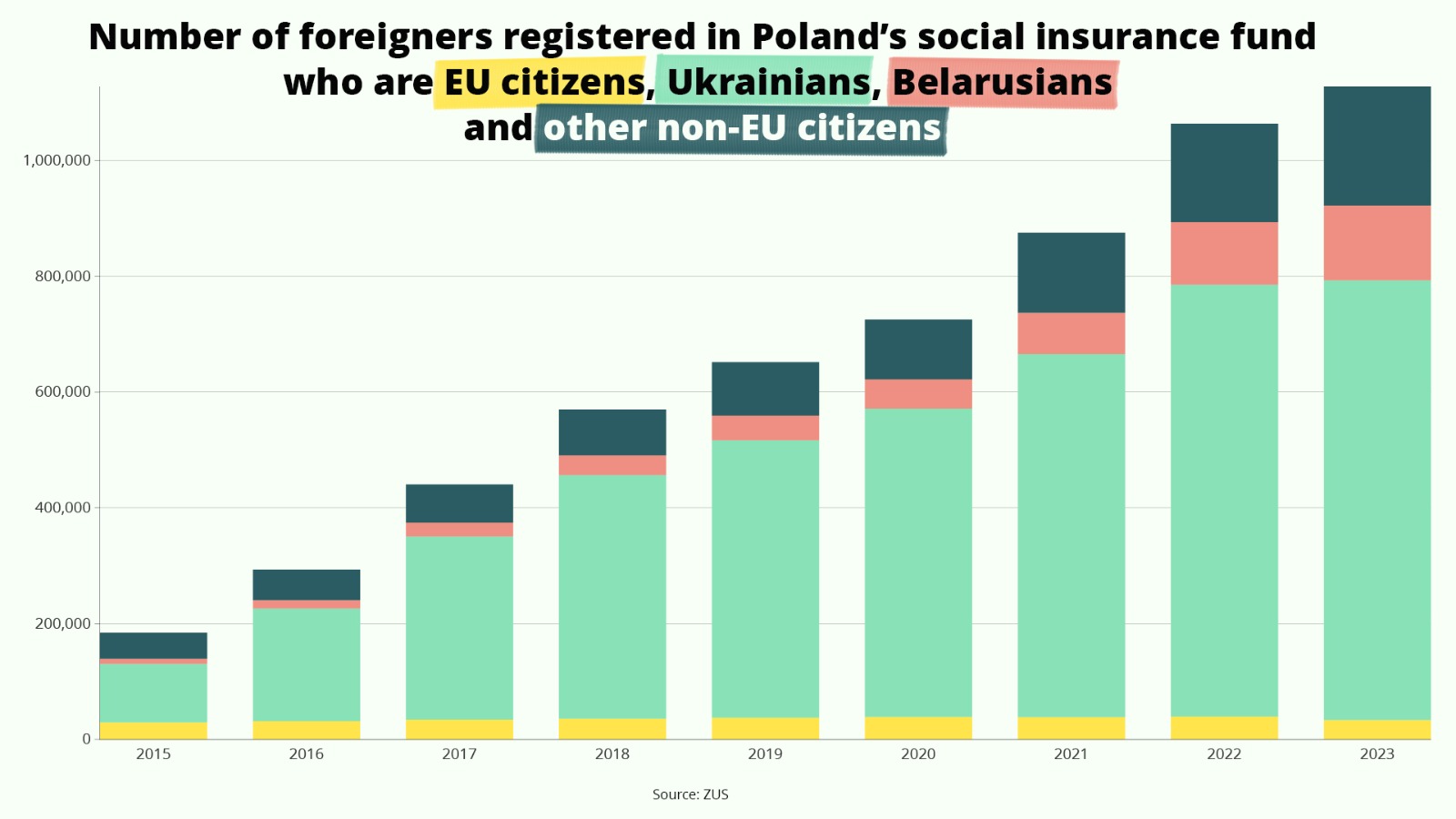

By the end of 2023, there were 1.13 million foreigners registered in Poland’s social insurance system (ZUS), making up almost 7% of the total.

Just as striking is that this mass migration happened largely during the eight years of rule by the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party between 2015 and 2023.

PiS came to power partly on the back of strident opposition to the reception of asylum seekers amid the European migration crisis of 2015-16. During its period in office, the party regularly used anti-immigration rhetoric. Yet at the same time, it oversaw the largest wave of immigration in Polish history.

At this point, an obvious caveat needs to be added: while PiS’s rhetoric was aimed largely at the alleged threat posed by migrants from the Middle East and Africa, the vast majority of those who have arrived in Poland are white and European.

Around two thirds of those 1.13 million foreigners in the ZUS system are from Ukraine, with the next largest group being Belarusians.

However, the numbers coming from beyond Europe have also been rising rapidly: last year, among the fastest-growing immigrant groups were Indians, Nepalis, Bangladeshis, Turks and Indonesians.

The contrast between rhetoric and reality under PiS was a dangerous mix. As the experience of Western countries shows, when voters hear politicians promising to clamp down on immigration but then see the number of immigrants growing, it fuels disillusionment and anger.

An example of PiS’s deceitfulness on this issue came last week, when – in a story first reported by Notes from Poland – it emerged that the current government is launching 49 new EU-funded “Foreigner Integration Centres”, designed to provide services to immigrants and help them adapt to life in Poland.

Some leading politicians from PiS, which is now the main opposition party, shared a tendentious news article claiming that the centres were evidence that Poland is “preparing for a surge in migration under the left-liberal coalition government led by former Eurocrat Donald Tusk”.

Such framing is triply dishonest. First, Poland is not preparing for a surge in migration, it is dealing with one that began under the PiS government. Second, the idea for the integration centres was conceived and piloted by the PiS government.

Third, PiS has regularly argued that migration is dangerous when immigrants do not integrate with the host society. So it should be pleased that such centres will help them do precisely that.

Poland is establishing 49 „foreigner integration centres” to help coordinate services for the country’s growing number of immigrants.

The EU-funded facilities will provide courses in the Polish language and adaptation as well as offering legal advice https://t.co/unuT7f5Bvv

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 11, 2024

However, Tusk and his Civic Platform (PO) party – which is the dominant force in the current ruling coalition – have also been guilty of treating immigration as a political weapon against its opponents rather than a serious issue that needs to be discussed.

In the past, PO was critical of PiS’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. But last year, amid campaigning for parliamentary elections, it pivoted on the issue and began to accuse PiS of being too soft on immigration, in particular by allowing large numbers of people from African and Muslim-majority countries to move to Poland.

“We are watching the shocking scenes of the violent riots in France and right now [PiS] is preparing a document that will allow even more citizens from countries such as Saudi Arabia, India, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Qatar, the UAE, Nigeria or the Islamic Republic of Pakistan to come to Poland,” said Tusk last year.

An attack ad published by PO just ahead of the elections, with its dramatic music and voiceover accompanied by pictures of Asian and African migrants, was reminiscent of the kind of material PiS itself had produced in the past.

Straszyli, straszyli, a sami ich wpuścili! #OszustwaPiS pic.twitter.com/oN1Ch49OyY

— PlatformaObywatelska (@Platforma_org) September 8, 2023

Those types of attacks on PiS have continued now that Tusk is in power. Last week, the prime minister announced a major speech that would outline a new national immigration policy.

In theory, such a policy would be welcome. Poland urgently needs to confront an issue that is becoming ever more pressing as the country’s shrinking, ageing population make immigration demographically beneficial, while growing wealth and record-low unemployment make the country an increasingly attractive destination for migrants.

But Tusk’s speech, at a PO convention last Saturday, did nothing to address such challenges. Instead, he used the issue to attack his opponents, accusing PiS of having been “the most pro-illegal-migration government in Europe” because of failings and corruption in the visa system under its rule.

The prime minister pledged to “regain control” of Poland’s borders and “ensure security” by, among other things, temporarily suspending the right to claim asylum – something that is likely to violate international law and Poland’s own constitution.

Poland will “temporarily suspend the right to asylum”, announced @donaldtusk in a speech outlining a tougher new migration strategy aimed at “regaining control and ensuring security”.

„I will demand recognition of this decision in Europe,” he added https://t.co/LJO1Nem1HE

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 12, 2024

Throughout his speech, Tusk said nothing about whether Poland needs immigration, what forms this should take, and how such immigrants should be integrated. Instead, he pointed to the “negative experiences” of Germany, which has shown that “if there are too many people of other cultures, then this native culture feels threatened”.

However, a few days later, things took a turn for the more constructive when Tusk announced that his cabinet – with the exception of ministers from The Left (Lewica), a small coalition partner, who voiced their dissent – had approved the new migration strategy, a summary of which was published online.

As well as containing the kind of tough rhetoric on security and asylum Tusk had already used, the document acknowledged in more detail the kinds of challenges Poland faces and how it can confront them.

That included the need to allow “the entry of foreigners to the labour market so that they can fill gaps” and to ensure their “inclusion and integration” in order to “allow their full potential to be used”.

Poland’s government has approved a tough new migration strategy that will include temporarily suspending the acceptance of asylum claims if „immigrants threaten to destabilise the state”

Four left-wing ministers voiced dissenting opinions against the plan https://t.co/xiCy3Qa052

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 15, 2024

Perhaps most importantly, the document begins by declaring that “our country has changed from a country of emigration to one of immigration”. That is a reality that politicians, and some Poles, have been reluctant to acknowledge. The fact that it is now being openly discussed and debated is a good thing.

Even better would be if the country’s two leading parties stopped using the issue as a means to attack and outbid one another, and instead took the opportunity to formulate a migration policy that can avoid some of the mistakes of the West and benefit both Poland and the millions of immigrants who already have or soon will call the country home.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: InPost press materials